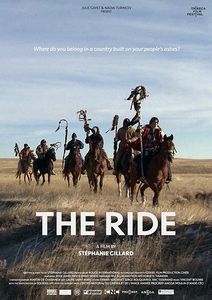

The Ride

documentary

RELEASE DATE: 2018-02-07

RUNNING TIME: 1h27min

DIRECTOR: Stéphanie Gillard

The Ride takes us along the annual 300-mile journey through the South Dakota Badlands, where young Lakota Sioux ride horseback and reflect upon the history of their ancestors, many of whom were massacred at Wounded Knee in 1890. This intimate, stunningly photographed account captures the thoughts and emotions of the young riders and the guidance and wisdom of the adults.

Trailer

director's note

Stéphanie produced and directed her first documentary “Une histoire de ballon” narrating the meeting between oral tradition and football in Cameroon (Awarded SCAM’s star in 2007 as well as jury prize during the 2007 Sport Film Festival in Palermo). She directed her second documentary in 2009, named “Les Petits princes des sables” co-produced with France Ô. Nowadays, Stéphanie Gillard keeps developing documentaries while working as a journalist and film editor.

“The Ride” is her first feature film destined to movie theaters.

How did you hear about this commemorative ride which happens every year in December?

A few years ago, fascinated by Jim Harrison’s books, I started reading all of his books. This is how I found a picture collection of which he had written the introduction. Images of Sioux riders in the blizzard, their faces covered by frozen bandanas or ski masks, going down a snowy hill. A group of riders carrying feathery staffs, riding along an icy road, followed by a line of old American cars. The silhouettes of three riders worthy of Edward Curtis appearing in a rear-view mirror… In these images, I found a thrilling beauty, something of today but still keeping a mythical dimension. Afar, horses, feathers and prayer staffs could make you think it was a century ago, as if those riders were going back on the warpath. But, up close, the signs are blurry, they mix with attributes of our era : parkas and beanies, pick-ups and gas stations, which tell us of today’s America. I, thus, tried to contact this group of riders by any means. These pictures had been taken 20 years ago, but I knew that this ride was still happening every year. Finally, I found a phone number, I called and a woman told me I just had to come.

How did you managed to be accepted by the Sioux?

I went a first time to participate in the ride in December 2009. I was a little shy, I knew that I was just a stranger to them, but after a few days, I started to be more at ease with the participants. I slept in the same gyms, I helped with the horses and meals as much as possible. I really wanted to live the adventure with them. Each day, they’d offer me to ride a horse, but I didn’t feel legitimate in this commemoration, I had the feeling of being the enemy's image. They told me that “no, it has nothing to do with it, it is part of the forgiving and memory process”. Nevertheless, I still preferred changing pick-up every day, talk with the guides, discover their history, their point of view and their reasoning being the ride. They told me about their lives, their childhoods. I discovered all that wasn’t said about native Americans: the forced school, the forbidding of their mother tongue and to practice their religion until the 70s, white people exploiting their reserve’s lands, natives who became cowboys, the difficult of being indigenous…

But it was no longer a list, it was the story lived by each person I met. They told me about it without complaining, without acting like victims. They asked why I was so interested in them even though they are “poor and are nothing”. They were very curious to know how us, French people and Europeans, thought of them. One morning, Jimmy crossed the gym to come straight toward me. I still hear his spurs ringing on the floor. He looked at me straight in the eyes and said: “Frenchie, I found you a horse, but, if you don’t want to ride bareback, you will have to find a saddle and reins…”. Another immediately lent them to me. I could not go back now. A 7-hour ride with a -20°C. And sleeping in the car despite the snow entering the passenger compartment. The day after Christmas, the blizzard came. We had to wait hours in the wind while holding our horses so they would not flee. Finally, after feeling like having survived a icy version of hell, we found our paradise in a small gas station with a liter of american coffee, potato chips and cigarettes. I already had an idea about the difficulty of this ordeal, but it was above all I had imagined. Barely a month later, in February, I came back a second time. I visited three reserves in order to see the people I had met during the ride. This second meeting was even more intense. They were surprised and happy to see me again, especially children. In general, people don’t come back to see them. Many of them think that the world doesn’t care about them. They were thrilled that I brought them a few pictures I had taken because many of the journalists that came never shown them what they had filmed or photographed.

I took the journey again in December 2010, and I came back during the summer of 2011 to spend more time with the Lakotas (Sioux), to learn even more about their habits and their life. Since then, we’ve stayed in touch… they have become my second family.

The Ride has been selected for the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. How did the meeting with the American public go, what were their reactions? Is there a political aspect to your movie?

I was very excited because Tribeca is a great festival! I was also anxious because I was wondering how people would react to a French woman talking about American history. In any case, the New York audience was very enthusiastic and touched! Many spectators asked me how to help the Lakotas. Showing the movie in the United States was very important to me. This movie deals with the journey in itself but also with the events that the riders commemorates : Wounded Knee is the last massacre which cemented the end of Native American wars. Due to its historical context, the film is therefore very political because it is not just any event in American history. The film helps to understand how history has shaped the present. During this trip, the riders tell us about their lives and what happened on this same road 125 years ago. They talk about what the US did to their nation, what they’ve endured : evangelization, acculturation, destruction of their language, theft of their lands in a constant and insidious way. During the fifteen days of the ride, these men takes a hold on their history, with their heads held high. They come out of the spirit of prostration in which the reserve is so often depicted. They are no longer victims, assisted persons, alcoholics, unemployed, suicidal, people with no future and no culture, but, by facing the cold, snow, hunger, but also in the eyes of others, they represent courage, solidarity and dignity. Galloping in the prairies, they return, for two weeks, if not warriors, then at least members of a people who were once free. They are recovering from their history so that it will not be forgotten, to express the importance of memory and to transmit it, along with their values, to the younger generation. It is a journey to become oneself, simply, to become Lakota again. This ride follows a trail of tears but it is lived by riders as a happy moment, which makes this story fascinating and thrilling. Consequently, this movie can touch everyone, because it shows a great example of humanity, generosity, courage and wiseness in a time where manners have a tendency to be forgotten.

Visually, your film is superb, especially when we know that you only had a few weeks to make it and that the conditions were harsh. Can you tell us more about the experience during the shoot?

We were a team of four people: Martin de Chabaneix (director of photography), Erwan Kerzanet (sound engineer), Carla Fiddler (Lakota rider who became a friend and was our driver), and me. In November, I presented my team to some of the riders and we followed the path of the ride so they could locate the riders would cross. We then cut out the riding sequences that we wanted to film in specific places, even though we knew very well that our plans might be compromised by reality. You can never be sure of the path the horses will take because the scouts change every day, and from year to year. They follow the road according to their memories of geography, and the landscape changes every year according to the amount of snow. We could not know how the weather would be. A snow storm could have disrupt the travel plans and complicate our shoot since Martin’s fingers would have probably froze! Not mentioning the fact that Jimmy was in an accident and that he had to go to the hospital of Rapid City where he spent two days and that AJ had to attend funerals… When you make a documentary, you can't hold people against their will, and things can change from one second to the next in this kind of epic. Apart from the unexpected, the biggest difficulties for the camera and sound were horses and pick-ups. We are not in a fiction, so we could never know what the horses were going to do, where the pick-ups were going to park… The second day, after shooting the clip with the bronc, Erwan made the decision to record the sound with a boom. Another difficulty was the end of the ride. After the riders’ arrival in Wounded Knee, there was a gathering in the Pine Ridge school. The next day, there was a ceremony at the cemetery of Wounded Knee but it was impossible to shoot because it is a sacred moment. After that, riders jump in their cars and go back to their homes, since for those living in Standing Rock, it is a 6-hour drive. I decided to stop shooting at the gathering in the Little Wound school. It made sense to end the movie with this dancing circle, since this form is very important in the Lakota custom and also because one of the origins of this massacre was that their ancestors were doing the ghost dance which was interpreted as a threat.

There was a particularly memorable scene in which three children are watching and commenting on a movie in a car, but we could not see which film it was. Can you tell us more?

It was Little Big Man by Arthur Penn. The children had brought the DVD of the film. On that cold day of rest in Bridger, there was nothing else to do. Then they settled themselves in our SUV and started watching it. We had to go to the gas station, so we took them with us. I was driving, but I saw this movie so many times when I was little that I just remember it by the soundtrack. I felt that this moment must have been in the film: young children watching their ancestors overthrow the American army. I looked at Martin and Erwan so that they would start filming and I was playing with the volume of the player.

In all your documentaries, children have an important place. Can you tell us why?

I get along very well with children and teenagers. I don’t know why… It is true that there is not much in common in my films (football in Africa, Tuaregs, Native Americans, fencing in the West Indies…). I can just tell you that Jesse has the same mischievous stare as Souley in “The Little Princes of Sand” or Stanjik in “Ultramarine Blades”. The funny thing is that film after film, my hero grows up, it's like I'm filming the same child, who, as time goes by, rises up around the world. They are all strong and solid characters with goals and who want to build their future. They are still innocent, but this mischievous little look they have tells me that they are aware of life's difficulties and that they know how to play with them. I was particularly inspired by the young Lakota that I met during my visits: Jesse’s frank smile that has no hidden motives and his love for horses, Wolf’s laugh when he sings in the middle of the night, Carla’s doubts about her future, TC’s seriousness when he talks about joining the army, Chang who was looking for me every time he wanted to play and Ramey who always invited me to dance. I shared unique moments with this young people. During the ride, we laughed, we cried, we were hungry and cold together. I heard their voices, doubts and stories. Even though they’re young, I was shocked by their maturity, especially for a childhood where they were given little hope of a promising future. I asked myself how could we live with such a strange duality: being American and Sioux as the same time, always asking yourself this question, to often being in the dark about the answer.

- 2004 : Une histoire de ballon (documentary)

- 2009 : Les petits Princes des sables (documentary)

- 2016 : Lames Ultramarines (documentary)

- 2018 : The Ride

Copyright © 2026 Ezekiel Film Production - All Rights Reserved - Legal Notice

Powered by Passion for the Arts

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience.