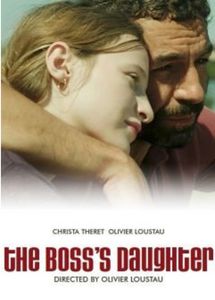

The Boss's Daughter

romantic comedy / drama

RELEASE DATE: 2015-11-15

RUNNING TIME: 98 min

DIRECTOR: Olivier Loustau

40-year-old Vital, a shop workman in a textile mill, is chosen as a "guinea pig" by Alix, 25, a consultant who has come to the factory to conduct an ergonomic study. What this quiet and secretive man does not know (and what nobody knows for that matter) is that the young woman is actually the daughter of Baretti, the boss. And what Vital did not expect (nor did anyone else) is that Alix would soon fall under his charm... Written by Guy Bellinger.

Trailer

director's note

The directorial debut of actor-turned-director Olivier Loustau “The Boss’ Daughter” presents a caring and knowing portrait of working class life in France: tts solidarity and, for all its bonhomie, limited prospect. Wrapped around the factory’s rugby team, it is the story of a man who makes a clean break with the past, his wife, job, friends, to have a second chance and lead another life, whatever it is, with the woman he loves.

One of the most striking points of “The Boss’s Daughter” is the lack of opportunity for its workers to live other lives, an opportunity which Vital seizes with Alix. I wonder if you would agree and comment on this.

Yes, I wanted to set the action of my first film in the working class setting where I grew up, and, in doing so, deal with the question of social determinism.

In the scene you talk about, Vital and Mado, his wife, try to talk to each other for once. They admit to each other that they are no longer happy together. Mado is resigned, thinking that it’s just fate and can’t see that Vital is giving her a last chance to do something for their life as a couple.

“The Boss’s Daughter” is about the meeting of two desires for emancipation: Alix opens a door for Vital, a door to another life. Vital allows Alix the opportunity to leave the nest as it was, get away from the invasiveness of her father’s love. Alix and Vital break out of their social straitjackets and create a realm of possibility for self-realization for themselves. I like to think that love can build bridges between two people who come from different social classes and create a utopic space, allowing them to escape from a seemingly preordained condition.

There’s a contrast in the film between the scenes of Vital with his wife, shot in closed spaces, sometimes claustrophobic places – the kitchen, stairs, in bed- and scenes with Alix, on the motorbike or in the countryside…

I wanted to set up contrast between the routine and dreariness of the daily grind and the notion of freedom, and carefree bliss of love that’s new, full of promise, to literally place on the screen inertia and speed.

The scenes of the factory, the textile machines are shot simply but with a degree of tenderness, as if scenes from a world which is disappearing. You’ve described the film as about the “end of a cycle,” which can be taken many ways and for many characters. Could you comment?

Industry and factory machines are on the wane in the French economy at present, and in this sense, workers are now somewhat like dinosaurs. We are at the end of an era for workers, and, in the film, for all the characters as a whole as well. It’s the end of a cycle for Baretti as a company, for Vital and Mado as a couple, for the relationship between Alix and her father, for the RC Tricot team… Alix is the detonator…

I wanted to capture the relation between man and machine, hence my choice of a modern factory, something graphic, full of color, something far removed from all the clichés generally associated with the working class world. It was key for me to film gestures, give the appropriate light focus to work, to show the poetry of all that…

The rugby world and the film’s rugby team, its games, parties, supporters, shirts, seems a rich metaphor for many things in the film.

Rugby is, for me, the collective sport par excellence, the one in which one cannot exist without the other person beside you, in which the individual is at the service of the collective entity around him. The values inherent to that sport seem to me those that sum up the best of the working class world: solidarity, courage, fraternity, self-sacrifice. Rugby also constitutes one of the last milieus in which one can encounter genuine social mixing, where there’s no concern about social, ethnic or religious origin. The only thing that matters is the jersey you wear and the colors you defend. It’s a family in the broadest sense of the word, where women also play an overriding role in the dressing room and in the stands. That’s why I wanted the rugby pitch to be the theatre where all the social conflict unfolds.

I believe the factory workers mixed professional actors and real workers, and the rugby team’s real players and actors. What were the benefits?

I wanted to remain firmly entrenched in reality, in order to be closer to the heart of the subject I was dealing with. In that sense, the non-professional actors brought the right tone at the outset, and the onus was then on the professional actors to adapt. We therefore managed to forge a very homogeneous group, made up of actors, real workers and rugby men, all of whom played and rehearsed together. That allowed for exchange, allowed us to break down the hierarchic codes of cinema. I learned that, alongside the likes of Abdellatif Kéchiche, who uses such a method, as Milos Forman used to do as well.

If the film is the end of the cycle, would you also describe it as the beginning of a cycle, in that Vital grows as a person, in his treatment of women, for example: His wife says tellingly: “I won’t fuck unless you’re nice and you can’t be nice unless you fuck,” but he’s much more caring with Alix.

Of course, at the end of the film, we are being ushered into a new cycle, symbolized by the couple, Alix-Vital. It’s the beginning of renewal. Vital has grown up throughout this story, in a far greater sense than in terms of his relationship with women. It’s much bigger than that. It’s got to do with a broader outlook on the world, with the expression of desires that had for long been buried or excessively hemmed in. And for Alix, there’s now a less naïve vision of the world on her part; she can now more purposefully express what she is: a young woman who can freely make her choices.

What were your main influences as a director?

There are many. I’ll start with Abdellatif Kéchiche, and the way he sets up the “play” as it were, comedy at the heart of the manufacturing process of a film. But I can also mention French poetic realism, (Renoir, Duvivier, Carné…), Italian directors like Ettore Scola, Pietro Germi, Elio Petri, Dino Risi, or present-day ones like Daniele Luchetti, in the way he focuses on the popular classes, their humor. I can also mention British social comedy, with its blend of social conflict and love stories. And, of course, Michael Cimino, in “The Deer Hunter,” which is such a wonderful portrait of the American working class.

Having worked with so many directors, some great, what were your main concerns when you set out to direct your first feature?

I tried to be faithful to my subject and avoid any form of pathos or any overly excessive sordid preoccupation with the sordid aspects of life. Working with the likes of Tavernier, Kéchiche, Nicole Garcia and Nicolas Boukhrief allowed me to learn a great deal through simple observation. I tried, most of all, not to forget how extremely lucky I was to be making my first film and to be able to enjoy doing it.

- 2015 LA FILLE DU PATRON

- 2010 FACE A LA MER (CM)

- 2000 C.D.D. (CM)

Olivier Loustau

Copyright © 2026 Ezekiel Film Production - All Rights Reserved - Legal Notice

Powered by Passion for the Arts

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience.